Biochemistry and cell biology aren’t things most cyclists get excited about, but a working knowledge of exercise metabolism is very relevant in cycling. Exercise metabolism consists of the pathways and energy systems employed to convert food to energy during cycling. So what is creatine phosphate? It’s part of that system.

What is Creatine Phosphate?

What is creatine phosphate? Creatine is an amino acid (methyl guanidine-acetic), produced by the liver, kidney, and pancreas. Creatine is naturally found in your muscles, red meat, and fish. Creatine phosphate or phosphocreatine, is a phosphorylated creatine molecule that serves as a rapid release reserve of high-energy. It’s used in muscle cells to store energy for sprinting and explosive exercise. Creatine shuttles high-energy phosphate from mitochondria (our power producers) to sites of muscle contraction.

Muscle Power

An energy-rich muscle has lots of creatine phosphate, whereas a fatigued muscle has little creatine phosphate. When extra creatine phosphate is stored in your muscles, you have that extra backup energy that helps you over the top of the hill or to power you through that last sprint to the finish line.

The ATP Connection

Understanding the function of creatine requires a basic knowledge of biochemistry. In a nutshell, creatine is part of a process that utilizes ATP.

Powered by ATP

Without going into too much detail that will make your eyes glaze over, ATP or adenosine triphosphate is quite simply the energy source molecule for all biological activity. When your muscles contract, it’s ATP that powers the activity. When cells grow and divide, that process is powered by ATP. However, ATP is not stored to a great extent in cells. So once muscle contraction starts, the making of more ATP must start quickly.

Three Phases of ATP

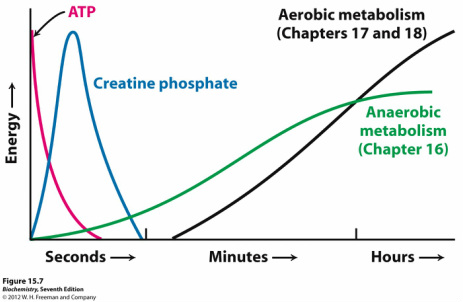

Since ATP is so important, the muscle cells have several different ways to make it. These systems work together in phases. The three biochemical systems for producing ATP are, in order:

- using creatine phosphate

- using glycogen

- using aerobic respiration

Using Creatine Phosphate

All muscle cells have some (not much) ATP within them that they can use immediately – but only enough to last for about 3 seconds. Because of this, all muscle cells contain and utilize creatine phosphate which is broken down to make more ATP quickly. Creatine phosphate can supply the energy needs of a working muscle at a very high rate, but only for about 5 to 6 seconds. Other studies have up to ten seconds.

Here’s Where it Fits on Your Ride

- The first moments of a sprint or steep hill, your muscle cells use the ATP they have within them.

- When that’s exhausted, your muscles switch over to the creatine phosphate stores to provide energy.

- If you still haven’t made it to the top of the hill or passed the next competitor, the glycogen system kicks in which then passes it on to aerobic respiration which is the release of energy from glucose in the presence of oxygen.

Rate and Volume

The daily turnover of creatine is about 2 grams for a 70 kg (155 lb) person. About half of the daily needs of creatine are provided by the body synthesizing creatine. The remaining daily need of creatine is obtained from your diet. Meat or fish are the best natural sources. For example, there is about 1 gram of creatine in half a pound of raw meat.

Creatine Loading

Dietary supplementation with synthetic creatine is the primary way athletes “load” the muscle with creatine. Daily doses of 20 grams of creatine for 5-7 days usually increases the total creatine content in muscle by 10-25 percent. Loading is typically done at this larger dose. Daily supplementation is much lower.

The Research

Research into creatine phosphate training has relied mostly on creatine with supplements rather than naturally occurring creatine. The results are based on extremely fast spin-ups such as a sprint, where at any moment a competitor can take off, sprinting away, requiring you to react quickly and jump along with them.

Are Supplements Good or Bad?

In their quest to run farther, jump higher, and outlast the competition, many athletes have turned to a variety of performance-enhancing drugs and supplements. Creatine is the most popular of these substance as it’s believed to enhance muscle mass and help athletes achieve bursts of strength. Creatine powder, tablets, energy bars, and drink mixes are available without a doctor’s prescription at drug stores, supermarkets, nutrition stores, and over the Internet.

The Claims

Supplement advertisers claim that supplemental creatine improves strength, increases muscle mass, and helps muscles recover more quickly. This muscular boost may help you to achieve bursts of speed and energy, especially during short bouts of high-intensity sprints. However, scientific research on creatine has been mixed. Some studies have found that while it does help improve short term sprinting, there is no evidence that creatine helps with endurance cycling.

Creatine and Glucose

Studies show that there is evidence that not all subjects respond to creatine supplementation. One study reported that subjects who experienced less of a change in resting muscle creatine did not appear to benefit from creatine supplementation. However, more recent studies indicate that taking creatine with large amounts of glucose increases muscle creatine content by 10 percent above when creatine is taken alone.

That Weight Thing

Creatine pulls water into your muscles which causes water-weight gain and makes muscles appear larger. Weight gain of about 0.8 to 2.9 percent of body weight in the first few days of creatine supplementation occurs in about two-thirds of users. Unless you have a specific concern—like hypertension that requires treatment with diuretics—it’s typically not considered a medical issue.

Cyclists and Creatine

Creatine is by far more popular in the gym than it is on the road. The bulk of it is used by weightlifters, assuming that the short bursts of power needed to lift weights can benefit from creatine. For cyclists, it’s up to you whether you need it or not. Some athletes treat it like a vitamin. A dose of 5 gram per day and you should be within the range of healthy supplementation. But as with any other change in diet, health or supplementation, always consult with a health care professional.